Population, Prosperity, and Technology

Why the Humane, Evidence-Based Story Beats Environmental Doom

For decades, much environmental thinking has centred on a deceptively simple idea: the pressure humanity puts on the planet depends on three factors – population size, wealth and technology.

This is intuitive. Impact increases if the population grows, if each person’s consumption increases, or if the technologies we use are dirty and inefficient.

This has often been summarised as the following identity: I = P x A x T, where I is impact, P is population, A is affluence, and T is technology.

Apart from this formula, what matters is that there are two very different interpretations of this basic idea: an outdated, neo-Malthusian interpretation and a modern, humane, evidence-based interpretation. These interpretations lead to opposing conclusions about the kind of future we should strive for and the policies we should advocate.

The Old Story: More People + More Prosperity = Disaster

In the 1960s and 70s, a pessimistic narrative dominated much environmental thought, popularised most famously by Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb.

The logic went like this:

More people inevitably strain the planet’s finite resources.

More prosperity means more consumption and therefore more damage.

Technology mainly amplifies harm, letting us extract and burn more, faster.

If every term in I = P x A x T can only make things worse, then humanity itself becomes the problem.

The implication was clear and disturbing: to avoid ecological collapse, both population and economic growth must be restrained – if necessary, by coercive means.

This worldview led to:

Calls for coercive population control and “optimal population” targets.

Hostility to economic growth.

Deep suspicion toward modern technological development.

Essentially, it was a neo-Malthusian narrative: the future was defined by scarcity and fixed limits, with collapse almost inevitable unless humanity abandoned the idea of universal prosperity and accepted living with far fewer people.

However, recent global development history has proven this view to be profoundly mistaken.

What Actually Happened: The Demographic Transition

If the old narrative were right, development and rising living standards would drive a permanent “population explosion”.

Instead, the exact opposite happened.

Across the world, as societies became wealthier, healthier, more educated, and more stable, people chose to have fewer children. In this demographic transition, societies move from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates as incomes and life expectancy rise.

So how did this happen?

Child mortality collapsed. Families could count on their children surviving.

Women gained access to education and work. They understood contraception.

Urbanisation raised the cost of large families.

Social security systems reduced the need for many children as “old‑age insurance”.

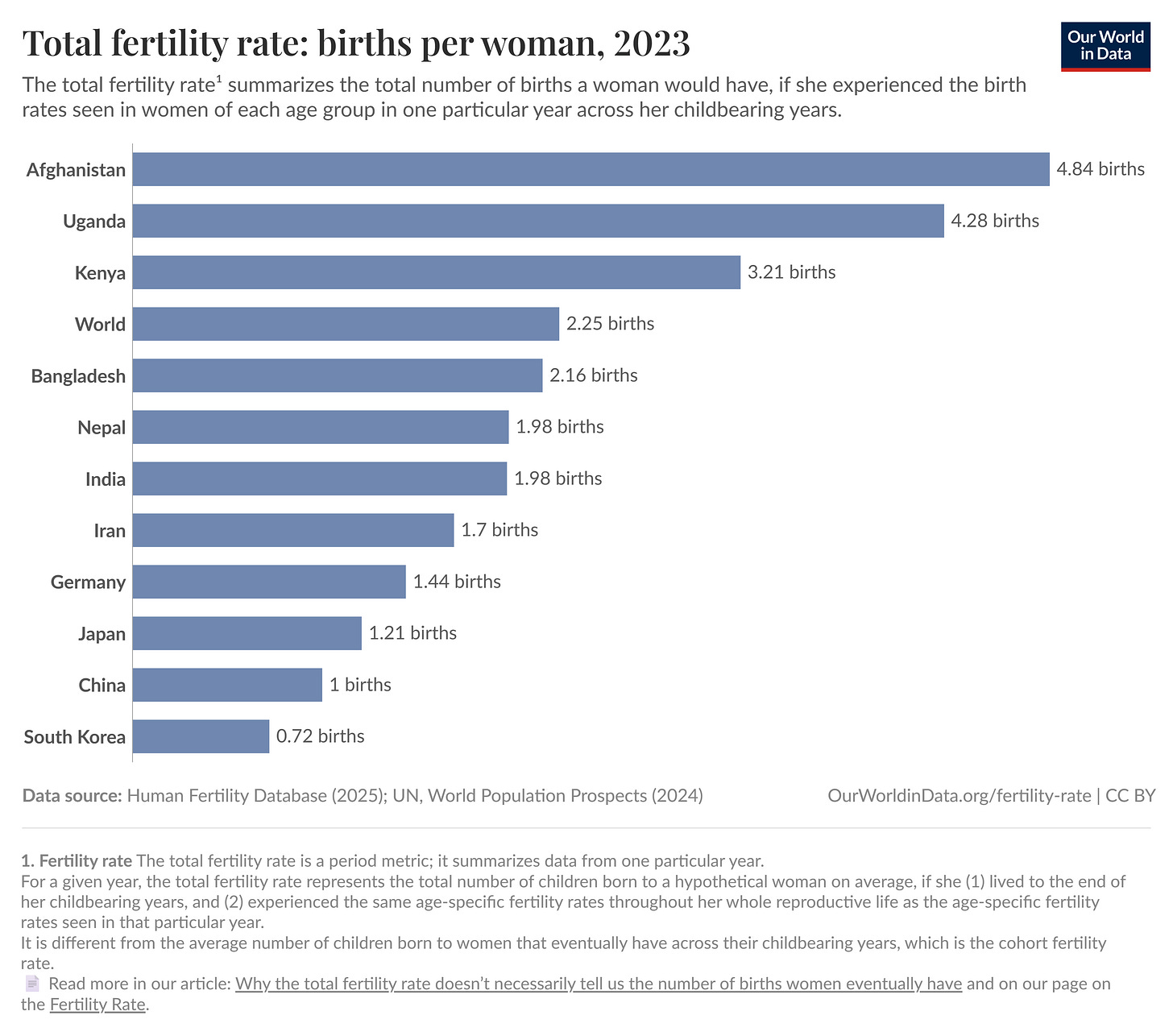

The result is a sharp decline in fertility rates. The global fertility rate has fallen from around five children per woman in the 1960s to below 2.5 today, with many countries now falling well below the replacement level of 2.1–2.2 children per woman. This includes several countries that most people would not expect to have a fertility rate below the replacement level, as the Our World in Data graphics below show.

Source: Our World in Data - The global decline of the fertility rate

This pattern is one of the most robust findings in social science: prosperity, education, and rights – in particular for women – drive fertility down.

China is the perfect case study: fertility was dropping fast even before the one‑child policy, and now China is desperately trying to reverse a dangerously rapid population decline. A different lesson comes from India, where the coercive sterilisation campaigns during the Emergency in the mid‑1970s provoked such a backlash that they helped bring down Indira Gandhi’s government in the 1977 elections.

The broader lesson is powerful: there is no humane, democratic way to “force” population reduction at scale. Population stabilises when people become healthier, wealthier, and better educated – not when states impose draconian controls.

Prosperity and Technology: From Threats to Tools

The traditional interpretation of IPAT saw both prosperity and technology in a largely negative light: increased income led to greater consumption, and new technologies simply magnified the scale of damage.

However, modern evidence tells a different story.

As societies grow richer, they do not simply consume more of everything. They also demand cleaner air, safer water, better infrastructure and protected natural areas.

Prosperity enables governments and citizens to invest in environmental protection and cleaner systems. However, this still requires active policies, regulations and innovations, rather than a laissez-faire belief that growth alone will solve all problems.

In practice, this has meant that:

Many richer countries have sharply reduced local air pollutants such as sulphur dioxide and fine particulate matter in recent decades.

Forest cover has stabilised or even expanded in several high‑income regions as agriculture has intensified and marginal farmland has been abandoned.

Environmental regulation and enforcement are generally stronger in high‑income democracies than in very poor states with weak institutions.

In other words, poverty is not green. Poverty forces people to burn wood and charcoal, clear forests, consume bushmeat, and use land inefficiently. Development brings the technologies and incentives needed for environmental stewardship.

The landscape of technology has changed significantly since the 1960s. Thanks to the Green Revolution, synthetic fertilisers, improved crop varieties and precision agriculture, global food production has soared without the need for proportional increases in farmland.

At the same time, modern energy systems and materials science are making it possible to “decouple” economic output from emissions and resource use:

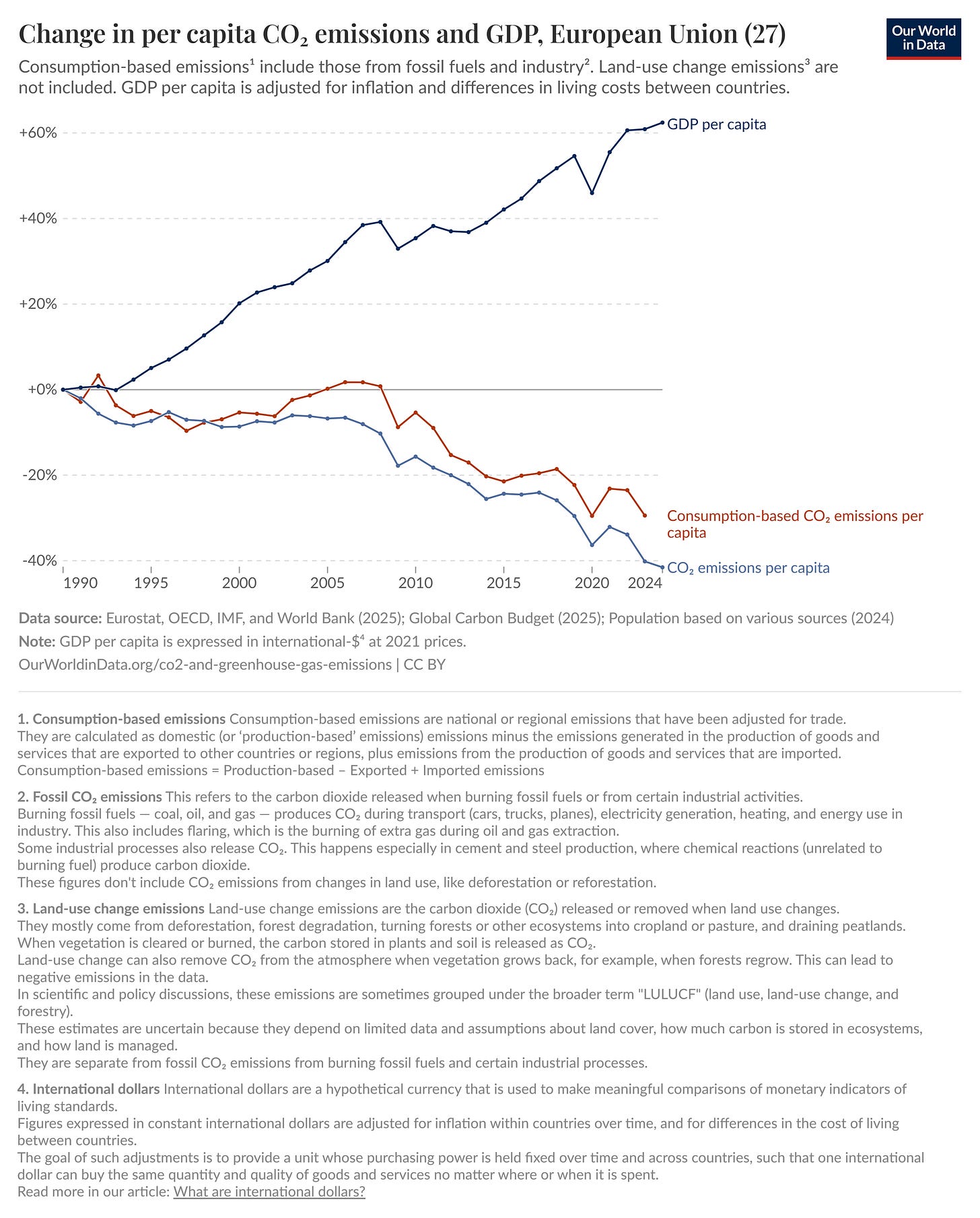

Many high-income countries have increased GDP while reducing territorial CO₂ emissions since around 2005.

Several economies show signs of absolute decoupling – emissions falling even as output continues to rise.

Energy use per unit of GDP has declined in much of the OECD, reflecting improved efficiency.

The following graph shows the decoupling for the European Union.

Source: Our World in Data - Change in per capita CO₂ emissions and GDP, European Union

This is not yet universal or fast enough, but the trend shows that growth and emissions are no longer locked together as they were in the mid-20th century.

In short, prosperity and technology are not inherently enemies of the environment. Used well, they become the main tools for shrinking humanity’s ecological footprint while improving lives.

Modern IPAT: A Humane, Evidence-Based Interpretation

The I = P x A x T identity itself is neutral; it is just a way to structure thinking about impact. What changed is our understanding of how each term behaves in the real world:

Population (P) does not grow without bound; it stabilises and can even shrink as societies develop.

Affluence (A), beyond a certain point, is associated with lower fertility and greater environmental capacity, not just more consumption.

Technology (T) is not a simple multiplier of harm; it is the main lever for decoupling output from emissions and resource use.

A modern, empirically grounded IPAT perspective, therefore, looks like this:

Prosperity is the best contraceptive. As incomes, education, and health improve, fertility falls sharply and voluntarily. Degrowth proposals that would freeze poor countries at low-income levels risk keeping them in the high-fertility, high-pressure phase indefinitely.

Affluence enables environmental stewardship. Affluent societies invest in clean technology, environmental regulation, and restoration. They move away from biomass and other destructive, low-efficiency energy sources towards more compact, cleaner systems.

Technology drives decoupling. High-yield agriculture reduces land requirements per unit of food. Low-carbon power, electrification, and efficiency gains reduce emissions per unit of GDP. Many high-income countries already demonstrate that emissions and GDP can move in opposite directions over multi-decadal periods.

In this modern view, two of the three factors – affluence and technology – can actually reduce environmental harm as they improve, and the third – population – is shaped by them in a benign direction.

The policy implication is not “less prosperity and less technology”, but smarter prosperity and smarter technology.

Two Worldviews, Two Futures

These two interpretations of the same identity lead to very different visions of the future.

The Old Neo‑Malthusian Story

Humans are inherently destructive.

Growth is dangerous and must be restrained.

Technology amplifies damage.

Coercive measures to limit population and consumption are required.

This story still surfaces today in rhetoric about “too many people”, “overshoot”, “ending affluence”, or strict “limits to growth”.

The Modern, Humane, Evidence-Based Story

As people become healthier and wealthier, they choose smaller families.

Prosperity gives societies the means and motivation to clean up and protect ecosystems.

Technology enables large reductions in pollution and resource use for each unit of well-being produced.

Human ingenuity is central to solving environmental challenges.

Humanity is not a plague that must be contained. Rather, humanity is the primary agent in building a sustainable and flourishing future.

This view is supported by demographic data, economic history and mainstream scientific assessments, including IPCC mitigation scenarios and UN population projections.

Why This Matters for the People and the Planet

Even today, some ecological and activist communities continue to be influenced by Ehrlich’s outdated thinking.

Messages that focus on ‘ending affluence’, romanticise poverty as ‘low impact’, or advocate coercive population control not only conflict with evidence, but also collide with core democratic and human rights values.

A modern perspective points in a different direction:

Development stabilises population. Countries move through the demographic transition as incomes, health, and education rise.

Prosperity improves environmental capacity. More affluent societies have more tools and stronger institutions for environmental protection.

Innovation enables decoupling. Clean energy, efficient infrastructure, and advanced materials allow growth with shrinking emissions and resource use.

This approach is more practical because it builds on existing trends. It is also more humane, as it is based on freedom, rights and opportunity rather than coercion.

Finally, it is more consistent with an open society because it avoids treating people, especially the poor, as the problem to be solved.

A Better Path Forward

If we take the modern, evidence-based interpretation of IPAT seriously, a more straightforward strategy emerges:

Support global development. Promote policies that lift people out of poverty, expand education – particularly for girls and women – and strengthen health systems. These are the engines of the demographic transition and the foundation of environmental stewardship.

Accelerate clean technology. Invest in low-carbon energy, efficient buildings and transport, high-yield and low-impact agriculture, and circular material flows. Technology is the main lever for decoupling, not a side issue.

Defend human dignity and liberal democracy. Reject coercive population policies and regressive “degrowth” ideas that would lock billions into poverty. Sustainable societies must be compatible with rights, pluralism, and individual freedom.

Challenge simplistic doom narratives. Acknowledge real risks and uncertainties while also recognising the documented progress in demography, health, and environmental performance. Fear can mobilise attention, but it is a poor guide to long-term, constructive policy.

Humanity is not the problem. Humanity – prosperous, educated, and technologically creative – is the solution.

Scientific Temper and Humane Environmentalism

So, what are the core commitments towards a better, evidence-based approach to elevate humanity and towards a liveable planet?

Place human welfare, dignity and freedom at the heart of environmental thinking.

Defend scientific temper – a mindset of critical inquiry and openness to evidence against denial and dogma, and promote science-based education from primary school level.

Embrace innovation and prosperity as vital tools for creating a sustainable future, rather than viewing them as threats.

The traditional IPAT narrative implied that saving the planet required turning against people, prosperity, and progress.

The modern, humane narrative, which is grounded in data, demography and real technological change, shows that it is precisely people, prosperity, progress and science-based education, beginning in schools, that can save both humanity and the biosphere on which we depend.

Readers wishing to explore these themes further will find a growing ecosystem of science-based, evidence-focused organisations. WePlanet advocates environmentally friendly, innovation-driven solutions, while organisations such as the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI, publisher of Skeptical Inquirer) and the German Gesellschaft zur wissenschaftlichen Untersuchung von Parawissenschaften (GWUP) promote scientific scepticism and critical thinking in public debate. Finally, Our World in Data and Hans Rosling’s Gapminder Foundation help us identify our misconceptions.

I also recommend reading another closely related piece posted today by Hannah Ritchie entitled ‘Can we break the human development–environment trade-off?’.

Further Reading

Breakthrough Institute. (2021, April 5). Absolute decoupling of economic growth and emissions in 32 countries. The Breakthrough Institute. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/absolute-decoupling-of-economic-growth-and-emissions-in-32-countriesthebreakthrough

Breakthrough Institute. Energy and Climate - Make clean energy cheap. The Breakthrough Institute. https://thebreakthrough.org/energy

Freire-González, J., Ho, M. S., & Managi, S. (2024). World economies’ progress in decoupling from CO₂ emissions. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 20545. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71101-2

Hepburn, C., & co‑authors. (2018). The long-run decoupling of emissions and output: Evidence from the largest emitters (IMF Working Paper No. 18/56). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/-/media/files/publications/wp/2018/wp1856.pdf

Our World in Data. (2014). The global decline of the fertility rate (M. Roser). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/global-decline-fertility-rate

Our World in Data. (2021). Many countries have decoupled economic growth from CO₂ emissions (H. Ritchie). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-gdp-decoupling

Our World in Data. (2025). China’s fertility rate has fallen to one, continuing a long decline that began before and continued after the one-child policy (H. Ritchie & E. Mathieu). Our World in Data – Data Insights. China’s fertility rate has fallen to one, continuing a long decline that began before and continued after the one-child policy

Scientific Temper. (2025). Scientific Temper 2025: Together with gbs for Critical Thinking and Education. Scientific Temper gUG. https://scientifictemper.org/en/news/scientific-temper-2025-together-with-gbs-for-critical-thinking-and-education

United Nations Population Fund. (2025). Understanding fertility decline: Developing rights-based solutions for achieving desired fertility. UNFPA. https://turkiye.unfpa.org/en/news/understanding-fertility-decline-developing-rights-based-solutions-achieving-desired-fertility

United Nations Population Fund. (2025). The real fertility crisis (State of World Population thematic report). UNFPA. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/swp25-layout-en-v250609-web.pdf