Fallacies That Undermine Science

When Morality and “Follow the Science” Go Wrong

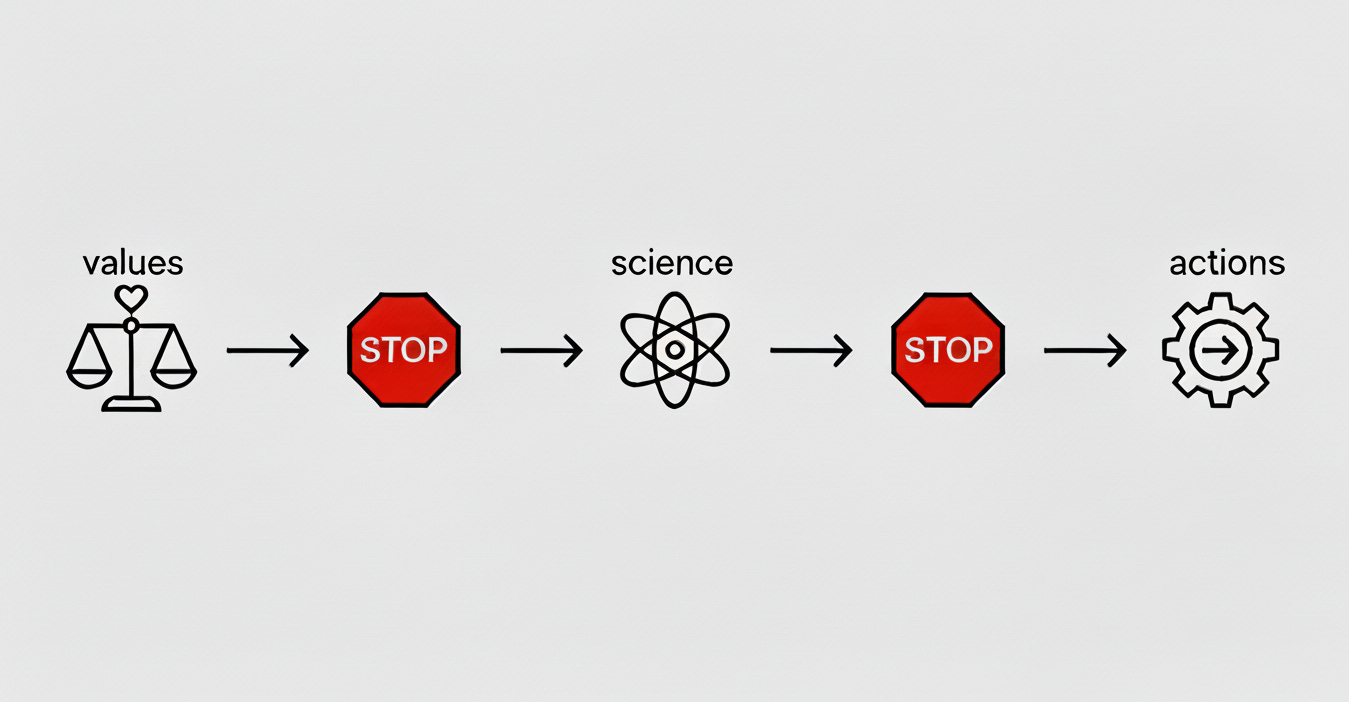

In philosophy, the naturalistic fallacy appears when people infer what ought to be done directly from what is the case—treating descriptive facts as if they carried their own moral instructions. The moralistic fallacy is the reverse: inferring what is true from what we want, fear, or morally approve of—letting “ought” to decide “is”.

Note: In an earlier version of this essay I called the latter the “idealistic fallacy”; “moralistic fallacy” is the standard term in the literature on metaethical logic and argumentation theory.

Both fallacies show up in current debates, but in different ways.

Moralistic fallacy: “Genetic engineering is unnatural and run by evil companies. It is therefore dangerous and must be rejected.” The undesirability of a scenario is quietly turned into a claim that it is dangerous or fraudulent.

Naturalistic fallacy: “Climate models and impact studies show serious risks. Science commands that we adopt this program.” Here, descriptive findings are treated as if they logically implied a unique policy, closing legitimate moral and political debate.

These are not just conceptual curiosities. They shape how people—from activists to commentators to scientists—talk about vaccination, climate risks, nuclear energy, population, agriculture, and much more. They also provide ammunition to those who want to undermine scientific disciplines.

The moralistic fallacy: wishing cannot make it so

The moralistic fallacy is very tempting in emotionally charged fields. It often appears in two logically opposite, but structurally similar, forms:

“Because we don’t like X, X is dangerous, cannot be true or cannot work.”

“Because we like Y, Y is benign, must be true or must work.”

X has often been nuclear energy or genetic engineering, while Y was renewables, “natural” medicine or organic farming.

Pessimistic environmentalists are so concerned about the risks of unconstrained human development that they treat abundant energy, industrial agriculture, or advanced technologies as inherently suspect, and therefore assume any promise of abundance must be illusory. Optimistic enthusiasts so deeply value economic growth and innovation that they believe climate risks must be modest, easy to engineer away, and that policies and interventions are neither needed nor even harmful.

Examples are easy to find:

Energy abundance: Critics claim that nuclear fission, nuclear fusion, or large-scale carbon removal “cannot work” or “will never happen” primarily because they dislike the idea of a world with cheap, dense, widely available energy. Their discomfort with abundance turns into empirical certainty about technical failure.

Food and agriculture: Others insist that genetically modified crops or intensive agriculture cannot help reduce hunger, not because the data say so, but because they associate “industrial” food systems with moral or aesthetic decline.

Free‑market absolutism: Some argue that free markets will automatically solve environmental and social problems and therefore view governmental or international climate policies as harmful intrusions that violate their core values of liberty and autonomy.

In all these cases, the moral or ideological story comes first; the “facts” are adjusted to fit, whether or not they are true. That is precisely what science should not be about.

Climate doomsday and the PIK Nature retraction

The recently retracted Nature paper by a team at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) is a revealing case where a dramatic, doomsday-like outcome was presented as far more certain than the data suggest. The study claimed that climate change could reduce global income by around one-fifth by mid-century. This finding was eagerly cited by central banks, the media, and activists as proof of catastrophic economic damage. Later scrutiny uncovered data problems (including flawed country statistics) and methodological issues in the statistical treatment of regional impacts. Due to the scale of the corrections and the increased uncertainty, the authors and the journal agreed on a full retraction and revision rather than a minor erratum.

Important points follow from this episode:

The retraction itself is a sign that self-correction is (still) working.

The existence of serious climate risks is not in question; the mainstream literature is clear that warming will have substantial effects.

But the originally dramatic framing was rapidly turned into a moral symbol—confirmation that “the system” is heading toward collapse—well before the robustness of the numbers had been thoroughly tested.

Once a result is embedded in a narrative of imminent disaster, it becomes difficult to disentangle evidence from expectation. When such a paper is later retracted, it is immediately weaponised by climate‑policy opponents as proof that climate science is driven by alarmism rather than rigour. The risk is not merely local; each high-profile exaggeration that fails gives those who are hostile to climate policy an excuse to doubt all climate research.

This is the cost of the moralistic fallacy when it operates inside science itself: hoping for firm, galvanising conclusions can tempt some researchers and communicators to oversell fragile results. When those claims collapse, trust does too.

Mainstream climate science and cautious voices

Against this background, the tone set by mainstream, methodologically cautious climate scientists is essential to maintain public trust in science.

Klaus Hasselmann, Nobel laureate for foundational work on climate models and detection–attribution, has always combined explicit acknowledgement of human-driven warming with insistence on transparency about uncertainty. He has emphasised that the signal of anthropogenic climate change emerges from natural variability in ways that can be quantified statistically, but has also stressed that long-term projections, and especially socio-economic impact assessments, are inherently uncertain and must be communicated as such.

Hans von Storch has likewise argued for methodological humility. He has been critical of scientists who present themselves as preachers of definitive truth, and of using extreme scenarios as if they were straightforward “business‑as‑usual” forecasts, given changing technological and policy trends. He has pointed out that if models systematically deviate from observations, the community must be ready to revisit key assumptions, rather than defending them as articles of faith.

Both exemplify a scientific attitude:

recognising the robustness of core findings (the reality and anthropogenic nature of warming),

clearly stating where uncertainty is significant, and

refusing to dress scientific results in the costume of moral certainty or political inevitability.

In an age where climate talk oscillates between denial and doom, this mainstream stance is neither tepid nor evasive; it is precisely what protects the long-term credibility of climate science.

The naturalistic fallacy: when science is treated as a moral oracle

If the moralistic fallacy smuggles “ought” into “is”, the naturalistic fallacy does the reverse: it tries to derive an “ought” straight from the “is”. In climate debates, this appears when people claim that science “tells us” which measures to take or even which political or economic system humanity must adopt.

Examples include:

The science of climate change proves we must adopt a degrowth agenda and dismantle capitalism.

Because we know that carbon emissions lead to global warming, science demands that we rely exclusively on renewables or even manage a transition by some date.

Since models show serious risks, any disagreement with this specific policy pathway is anti-science or denial.

Science can tell us that greenhouse gases trap infrared radiation, that doubling CO₂ raises equilibrium temperature by a specific range, that different emissions scenarios lead to different risk profiles, and that some technologies are more effective than others at reducing emissions. It cannot, by itself, tell us whether we ought to prioritise speed over equity, how to weigh short-term costs against long-term benefits, or which mix of values (freedom, security, equality, innovation, stability) society should adopt.

When activists or commentators present a particular ideology—whether radical degrowth, total system transformation, or, on the opposite side, unbounded techno‑optimism—as “what the science says”, they turn science into a moral authority it cannot be. This not only misrepresents the nature of scientific inquiry; it also hands critics a powerful line of attack: “If ‘science’ tells me what to think politically, maybe science itself is just politics.”

The naturalistic fallacy thus damages the same thing that the moralistic fallacy does: public trust in science that is distinct from political and moral advocacy.

Science at large is at risk, not just climate science

Climate science may be the most visible arena where these fallacies play out, because it sits directly at the intersection of physics, economics, ethics, and geopolitics. But it is unlikely to remain the only one. The same patterns are already emerging in other fields.

Two obvious candidates are:

Public health and epidemiology: During the COVID-19 pandemic, scientific findings about transmission, masks, vaccines, and lockdowns were rapidly absorbed into tribal identities. Some actors overstated certainty or downplayed trade-offs, insisting that “the science” dictated a single policy path. Others rejected basic epidemiology because it clashed with their political preferences. The result was a collapse in shared trust: people on all sides began to see epidemiology less as a neutral discipline and more as a weapon in culture wars.

Genetics and sex/gender biology: Research into biological sex, intersex conditions, and gender identity has become highly politicised. Some actors try to derive social or moral norms directly from biological findings. Others confuse sex (biological) and gender (identity/roles) and wrongly claim that ‘sex is a spectrum’ in a way that ignores the fundamental anisogamous nature of sexual reproduction in most animals and plants and all mammals, where two distinct gamete types (eggs and sperm) define the basic male–female categories and intersex variations are exceptions rather than a third type.

If the climate arena normalises a pattern in which every methodological dispute is treated as a political betrayal, and every attempt at nuance is read as denial or alarmism, these habits will spread. Once the public begins to see all of science as a series of tribal narratives, the gains of the Enlightenment—shared standards of evidence, cross-cultural reproducibility, the possibility of correcting errors—are at stake.

In that sense, climate science may be only the first apparent victim. If allowed to metastasise, the same logic could engulf fields from ecology and demography to psychology, nutrition, and AI safety.

Why avoiding both fallacies is essential

If trust in science is to survive, both the moralistic and naturalistic fallacies must be resisted.

Keep facts and values distinct, even when closely related

Facts inform values: knowing the likely impacts of warming, or the comparative risks of different energy sources, should shape our moral and political reasoning. Values guide how we respond: science cannot tell us how to trade off present costs against future harms, or which distribution of burdens is just. Recognising this division does not weaken the case for climate action; it strengthens it by making the reasoning explicit rather than smuggling politics in under the banner of “what science says”.Guard against wishful thinking in both directions

People on all sides of environmental debates are vulnerable to the cognitive bias of believing what they want to be true, rather than what the evidence supports. Those who advocate for ecological restraint should resist the temptation to assume that technologies they distrust cannot work, regardless of the empirical record. Supporters of free markets should not assume that market forces will always overcome physical or ecological limits. Markets tend to be most efficient at allocating resources over relatively short time horizons and often discount or ignore long‑term environmental externalities. The real world is constrained by biophysical laws, not by ideological narratives, and ignoring these constraints is itself a form of wishful thinking.Present uncertainty honestly, without paralysis or drama

Many mainstream climate scientists show that it is possible to be both frank about serious risks and rigorous about uncertainty. Their example should be the norm: clear on established results (e.g., the basic greenhouse effect), transparent about where knowledge is limited (e.g., regional impacts, extreme events), and honest about the fact that different value frameworks can lead to different policy choices even when everyone accepts the same evidence.Protect science as a universal attitude with robust methods, not as a partisan tool

The more science is presented as “on the side” of one political tribe, the easier it is for others to reject it wholesale. Science must remain open to critique, replication, and revision from all directions and must welcome disagreement about policy, provided it does not involve denial of basic empirical facts.

If we fail to do this, climate science will not be the only field to suffer. Once trust in science is replaced by suspicion that every claim is merely a vehicle for someone’s cultural project, the very idea of objective inquiry becomes fragile.

Scientific temper asks for something more demanding but more hopeful: to accept that reality is not obliged to match our wishes, and that our moral commitments, however sincerely held, do not confer automatic authority on our factual claims. That discipline—distinguishing what is from what we want and what we ought to do—is hard. But it is also the only way to preserve science as a genuine common language in a fractured world.

Support Scientific Temper

If you value this work and want to help promote scientific temper, please consider supporting our non‑profit organisation.

Further reading

The Nobel Prize (2021). Interview: Nobel Prize in Physics 2021 – Klaus Hasselmann. NobelPrize.org.

Jaeger, C. C., & Jaeger, J. (2022). Klaus Hasselmann and economics. Journal of Physics: Complexity, 3(4), 041001.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732–735.

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government (Yale Law School Public Law Working Paper No. 307).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A., & co-authors. (2024). The economic commitment of climate change. Nature, 628, 123–129. (Retracted 2025).

Retraction Watch. (2025, December 3). Authors retract Nature paper projecting high costs of climate change. Retraction Watch.

von Storch, H. (2009, March 22). Klimawandel-Essay: Am Ende des Alarmismus. Der SPIEGEL.

Welsch, H., & Biermann, P. (2022). What shapes cognitions of climate change in Europe? Climatic Change, 170(1–2), 1–23.